Hi List friends,

Nice to see the new platform, thank you so much, Andrew. You don’t spare your time and your energy !

The better side of the Coronavirus infection is : there is plenty of time to think, to read, to play and even to record.

I’m spending some time recording every 2 or 3 days some pieces I’m pleased to show because of some interpretation questions they raise.

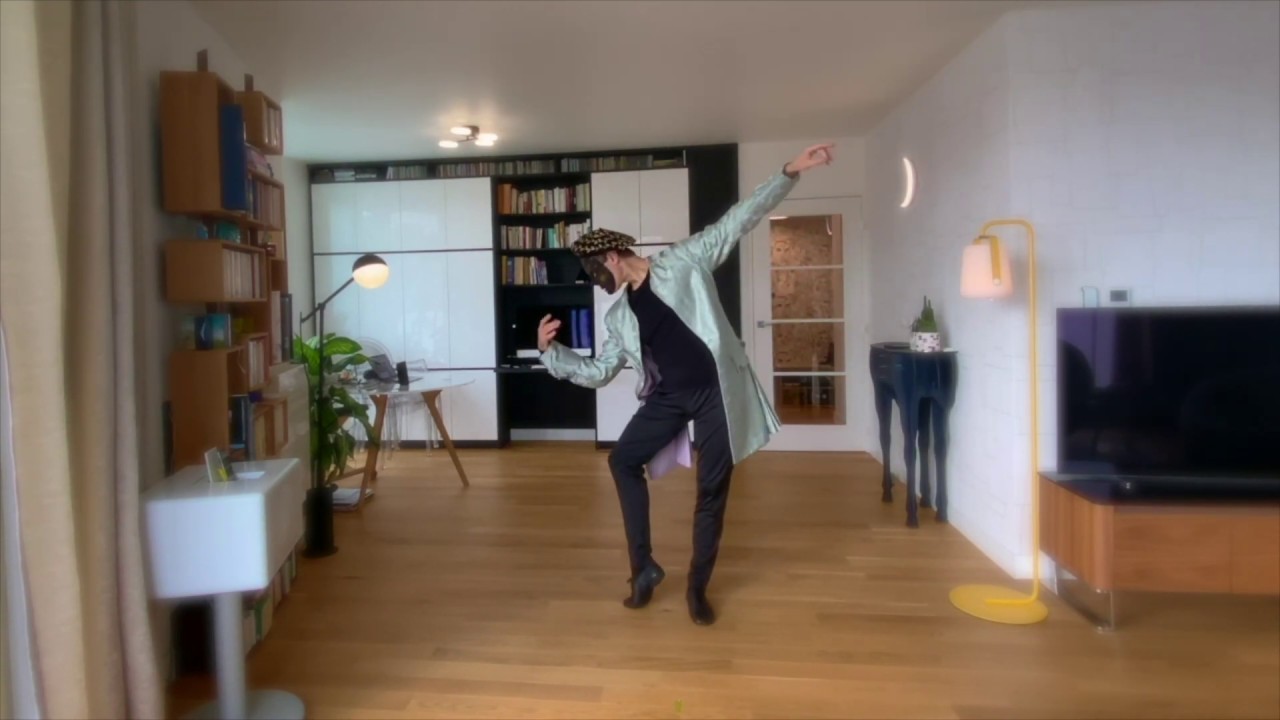

And mainly dances.

The relationship between elaborated music and dance is a book that largely remains largely to be written

This is just a contribution. As musical « mouvement » (Bewegung, « how, in which way »)) is usualy confused with « tempo » (how fast). Everybody knows about the expression « Les Caractères de la Danse »., but discussions are mostly about tempo and interpretations often say : I actually don’t really know how far this has something to do with dance. Treatises give some tempo indications for dances. But the mouvement cannot really be explained : it’s something people feel in their body, it’s in the air . Non si può spiegare…

When I’m working (conducting, teaching) with ensembles and orchestras, the main problem is usually to get the right and common sense of the mouvement (Bewegung, motion) of the « mouvement » (a piece based on an unifying « mouvement » or motion). Once this is solved, everything becomes easier if not easy, logical, self-evident, and, like in repertoires of oral tradition, several musicians play after a short while well together.

The other way is to solve many small, particular problems, explaining a lot, and usually, this makes things much more difficult and sometimes we don’t really reach the goal - though its sometimes interesting, if not exciting, or funny.

Early music spends hours, books and huge efforts explaining before one is allowed to play through, because the most important is to be « Highly Informed ». Reaction against musicians of later repertoires who just play first… (actually it’s not true). This is, deliberately, kind of a caricature (not sooo much - but it’s such good news to see how much the art of improvisation is developing among early musicians, in Basel e.g… This sheds a new light on another way of approaching early music.

It’s interesting to notice that, when we perform Monteverdi, Bach, Couperin, even Mozart, we are reading from parts without numbers or rehearsal marks, with very few dynamics and phrasings. And musicians often didn’t rehearse a lot (parts of the Ouverture of Don Giovanni were completed some hours before the première, but the change of tempo is supposed to be 1/2, that makes it feasible with few words before playing). It was a kind of oral tradition, everybody was aware of the style, like Tango or Walzer players in Argentina or in Vienna. Reconstructing it needs to think, to write on the score (what people didn’t do), but as soon as possible, to be able to forget theories, marks, temperaments and, according what Leopold Mozart says : you need to c onsider Character, Tempo AND Mouvement (« die Art der Bewegung » : dance, dance-like motion, dramatic gestures etc) AND PLAY, once the base, the project are clear. And, like in baroque grounds, in folk music, in jazz etc, people « just speak, play » because they feel a clear structure, they are breathing the same air. It’s in the air.

My concern is : when listening to « HIP » performances today, it seems to me that the basic structures of baroque declamation, versification and dance (that have very much in commun) are drowned under mountains of discourse on aspects that are not essential (though interesting discussing) for the interpretation of great works. And, like about philosophy, sociology, or languages, our understanding of the past OR of the present state depends a lot of the comparison and relation we are able to find out between earlier and later evolutions, because there are constant principles that underlie the evolution and allow a better understanding of diversity according to the epochs (mutandum est mutanda. But if you think everything’s different, in another time and you need to forget everything, even of later periods, you throw the baby out with the bathwater. Relation between music and dance and theater and verses are constant since Aischilos, and until the beginning of the 20th century, and are still present in oral traditions.

This is, I think, what we need to investigate further. It will change the way we perform Frescobaldi, Scarlatti, Couperin, Bach and even the classical and the romantic repertoire (actually : I never heard a pianist who was totally wrong by playing Hungarian dances or Chopin’s Polonaises : why are we happy with sarabandes that are just very slow 3/4 pieces that have nothing to do with the motion, the typical gestures, the character of a sarabande ? But comments on : articulation, the hps, the tuning etc.

This makes me propose some readings in order to make clear, as far as possible, as well as possible as for homework, my experience of the relations between dance and music, and how the rhythm of dance shapes the whole Baroque language, and how it affects even Bach’s most elaborated works (in the Partitas, but also in dance-like pieces, cantatas, since Bachs was obsessed by syncretism.

We are at the beginning of this project. I hope I’ll have time to develop it as much, as long I’d like. I am at home like you, maybe, but I also retired from regular teaching. So…

A blog will come later.

Sorry for being long (just today), for my approximate english.

Vivete felici !

and take care.

please go to :

the quality of the sound will be better and better !

There are more exemples in my recording of Bach’s Partitas. But the late Bach should be the final step.

This is another problem of pedagogy : we are often starting with the last variations, the most elaborated ones (that’s what Bach is in the evolution : the most complicated state, the most intricated one, which accustoms young (who become older !) to read the music as closely as possible to the text, as children recite prayers as best as possible whilst forgetting or without always understanding what it is really about). Since in some way, it’s often difficult to find the theme in the last variations (Godberg, Beethoven !), but we like to admire complexity and sometimes forget that there is a simple and clear base that makes things much more understandable, and… not as difficult as we believed : the theme, the structure of the song, the dance…