Claudio,

I guess you base your assertion in your U.T. that Rousseau had three just thirds in his pattern on his wording “once you have arrived at the sharps” [“dès qu’on est arrivé sur les dièses”]. I am not sure that is warranted in view of the fact that he is clearly plagiarizing d’Alembert to the extent of using precisely the same words in most cases. (I think I wrote it the other way around in my earlier post, saying d’Alembert plagiarized Rousseau).

Rousseau adds a little more detailed description in places, and that instance of “when you reach the sharps” is one of them, but the fact that he reproduced exactly d’Alembert’s error (D flat when he meant E flat - and d’Alembert corrected the error in the second edition) suggests to me that Rousseau was not terribly sharp in these matters, thus not really a trustworthy source.

I find it amusing and telling that both of them describe tuning in the flat direction from C, citing F, B flat, “et cetera.” Why not write the words E flat? That’s the only additional note that hasn’t been tuned. Apparently it is because d’Alembert was thinking in terms of F, B flat, E flat, A flat, D flat, since he writes D flat as the proof note in relation to G sharp. Would any musician who actually tuned his own instrument make that mistake? Would any musician reading d’Alembert’s mistake fail to notice it and reproduce it in a Dictionary entry? Their mistaken notion that there were five rather than three fifths remaining to be tuned in the flat direction makes a little more sense out of how they describe them.

All told, I don’t think we should take Rousseau or d’Alembert as gospel with respect to their details, especially considering that d’Alembert was not a practicing musician, and Rousseau was more dilettante and theoretician than performer. d’Alembert probably consulted with a practicing musician, and didn’t quite get all the details right. Rousseau plagiarized and expanded on d’Alembert. Their evidence is useful, as it is the most detailed that has survived, but it is more suggestive than definitive.

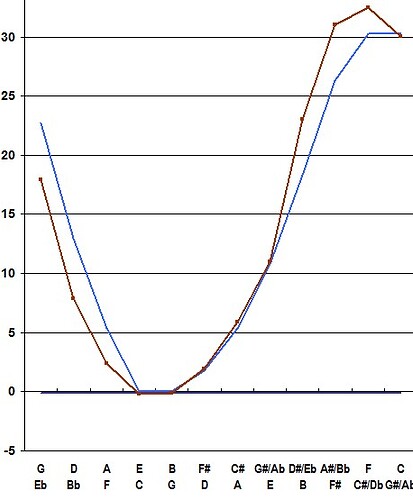

What we can derive from the two of them is a pattern that probably has some connection with actual practice at the time: that the CE third should be just (or close), and that some of the 5ths in the flat direction from F or B flat should be wide, at least two of them, possibly all three. And that the thirds will become somewhat wide in the sharp direction (as the fifths are tuned less narrow), and considerably more wide in the flat direction (as the fifths are tuned wider in a pretty rapid progression - there are only three of them between C and E flat.) It is quite likely that what was actually done was more random and varied than that.

For those interested, here is my Rousseau text:

“Pour cela, premier on commence par l’ut du milieu du clavier, et l’on affaiblit les quatre premières quintes en montant jusqu’à ce que la quatrième mi fasse la tierce majeure bien juste avec le premier son ut; ce qu’on appelle la première preuve. Second En continuant d’accorder par quintes, dès qu’on est arrivé sur les dièses, on renforce un peu les quintes, quoique les tierces en souffrent; et, quand on est arrivé au sol dièse, on s’arrête: ce sol dièse doit faire avec le mi une tierce majeure juste ou du moins souffrable; c’est la seconde preuve. Troisième On reprend l’ut et l’on accorde les quintes au grave, savoir, fa, si bémol, et cetera, faibles d’abord; puis les renforçant par degrés, c’est-à-dire affaiblissant les sons jusqu’à ce qu’on soit parvenu au re bémol, lequel, pris comme ut dièse, doit se trouver d’accord et faire quinte avec le sol dièse, auquel on s’était ci-devant arrêté; c’est la troisième preuve. Les dernières quintes se trouveront un peu fortes, de même que les tierces majeures; c’est ce qui rend les tons majeurs de si bémol et de mi bémol sombres et même un peu durs; mais cette dureté sera supportables si la partition est bien faite; et d’ailleurs ces tierces, par leur situation, sont moins employées que les premières, et ne doivent l’être que par choix.”

d’Alembert:

“On commence par l’ut du milieu du clavier, et on affoiblit les quatre premieres quintes sol, ré, la, mi, jusqu’à ce que mi fasse la tierce majeure juste avec ut; partant ensuite de ce mi, on accorde les quintes si, fa #, ut #, sol #, mais en les affoiblissant moins que les premieres, de maniere que sol # fasse à peu près la tierce majeure juste avec mi. Quand on est arrivé au sol # on s’arrête; on reprend le premier ut, on accorde sa quinte fa en descendant, puis la quinte si bémol, et cetera et on renforce un peu toutes ces quintes jusqu’à ce qu’on soit arrivé au ré bémol, qui doit faire en descendant la quinte juste, ou à très-peu près, avec le sol # déjà accordé.”