I guess David’s home temperament is a bit like my Belder I. No need to discuss how this is built up. It varies every time a bit. And sometimes you don’t have a lucky day and it won’t be very nice. Or it takes you twice as long…

PJ

Guess we are having no more replies, so here goes mine. Will post a final statistics shortly.

- Frequency: It varies according to my activities, but every two weeks is average, occasionally retouching the worst offending 4’ strings.

As for time needed, my instrument is a double chromatic FF-g’’’, with 189 strings.

I use printed schemes, with no electronic aids and no metronome for beat counting. - Time needed: I like to retune every string (even when almost perfect) and prefer a leisurely pace, with about 5 minutes for the partition, 25 minutes to complete the 8’ choirs, and 10 minutes for the 4’ stop. Total 40 minutes. (If in a hurry I can do it in 30 minutes).

- Temperament: When working mainly on middle-to-late Baroque music by French composers, for months on end I tune to Standard French Temperament (Rousseau’s ordinaire). When I am working mainly on German Baroque composers, I use Barnes’s Bach temperament.

What would do you use for Scarlatti? (is there one temperament good for all of Scarlatti?)

Dear Domenico, in my opinion (have not done any specific research on this) any German-type Good temperament is suitable for all D. Scarlatti, and statistical research by Sankey and Sethares (1997) showed that best fit is achieved using a modified 1/5-comma meantone or, quite similarly, Vallotti or Barnes. As per my UT book p.180, Essercizi 1 to 18 are consistent with meantone with 2 split sharps (14 notes per octave). However, from K.19 onwards most sonatas show clear tell-tale marks of a fully circular 12-note temperament.

MEMBERS’ TEMPERAMENT: THE STATISTICS

I am pleased to report the statistics about the replies kindly sent by our members.But first a few clarifications are in order.

A first difficulty is in the definition of a temperament. When a member writes “meantone” I assume the most common variant, 1/4 (syntonic) comma. Historically some temperaments were described with accuracy: we all agree on what “Werckmeister III” means. But there were significant variants of the French 18th c. “temperament ordinaire”. I will clarify any doubt in the statistics.

I have counted David Bedlow’s tuning as a modified 1/5-comma meantone (although it differs from the usual way the fifths are enlarged). Jonathan Addleman alternates between no less than 4 different temperaments with no clear preference, so I have not entered his reply for Temperament, but I have for frequency and duration. When Davitt tunes his muselar to meantone with “major thirds slightly larger than pure” I have assumed 1/5-comma meantone. When Tilman tunes a modified 1/4 meantone, I assume Rousseau that is a good average between the historical variants.

Some members in their replies reported using more than one temperament: if one is reported as usual and another as rarely used, the usual is counted in the statistics below. When a member has different instruments tuned to different temperaments or else alternates between long periods with different temperaments, every single temperament is counted in the statistics.

Time-needed statistics: I am disregarding virginals which, being one-choired, take much less time to tune.

THE STATISTICS

Members who responded: 15.

Harpsichords tuned: 19.

Frequency of tuning: average once every 22 days.

Time taken to tune a harpsichord: average 41 minutes.

Temperaments used:

3 x 1/4-comma Meantone

1 x 1/5-comma Meantone

1 x Rameau’s ordinaire

2 x Rousseau’s ordinaire

2 x Modified 1/5-comma meantone

1 x Tweaked Werckmeister III

2 x Vallotti

1 x Belder 1

1 x Kirnberger III

1 x Kellner’s Bach

2 x Barnes’s Bach

1 x Lehman’s Bach

2 x Almost Equal

And while we harpsichordists strive for an authentic rendering of the beautiful sound of meantone, or else the diversity of affects caused by modulations in circular temperaments, it is sad to see recent first class performers of JSBach Passions playing in Equal Temperament: this is apparent by the fretted instruments in the famous “Es ist vollbracht” aria, starting around 1:16 of this video:

Sorry I am replyng after you collated the results! I have no free time between my various lines of work and the demanding spring garden and my animal companions needing love, care, walks, and play and cuddling, thank heavens for them!

- I have many harpsichords, a clavichord, a fortepiano, various historic pianos. Obviously the ones at my second location wait for my arrival for tuning. Wherever I’m in residence though, tuning is generally restricted to immediate or upcoming needs. Instruments going out for rentals get a good tuning and check over 1-2 weeks before they go out and a fresh tune the day before, plus obviously tunings for rehearsals and performance. Those probably don’t fit well into this statistical survey. Tunings depend upon the client.

If I’m having rehearsals with my group, I tune the relevant instrument regardless, so that probably isn’t relevant either. My band members and myself appreciate knowing consistently where to place their notes.

My English bentside spinet, clavichords, my Flemish double harpsichords, my French, double and single manuals, my Italian and my Acker/Zuckerstein fortepiano almost never go out of tune or not far, a testament to my climate control and stringing designs? Luck?. My German harpsichord is awaiting restringing with proper brass wire from Stephen B., which I’m hoping will resolve it’s tuning issues. When I’m using it, it needs tuning for my purposes weekly. More generally though, for my own purposes, I would say I tune the most used harpsichord every 1-2 weeks until I can’t stand it and I have an annoyingly particular ear.

-

Depends upon the size, but I’m very fast at tuning. 15-25 tops for a harpsichord or clavichord, longer for the fortepiano. My speed has been honed by needing to tune many instruments every day for the Boston Festival during the limited quiet time before opening and tuning during act breaks for the Florida Grand Opera.

-

Temperaments vary. Italian and virginals in 1/4 comma. small clavichord in 1/4 comma. I am quite found of the Bach/Lehman temperament which works well for a lot of repertoire and is fast to tune by ear if I’m lucky enough to have a quieter environment for tuning and to quickly check the intervals in a noisy environment. If I’m in an exclusively French mood I’ll go for a French ordinaire type called either Anne 1 or Anne 2. I am rarely in an exclusively French mood. Obviously if the artists for a concert rental have a preference or requirement I tune in that. Modern orchestras with modern instruments and mind set get equal or an “almost equal” that suits what is being played.

Kirnberger? never unless the artist wants it. LOL

Best! Back to work here!

Anne

Claudio, you forgot to mention who won the prize for the slower tuner… (me ![]() )

)

Dear Domenico. Do not feel ashamed at all for performing a task carefully. Of course, some harpsichordists have reported tuning a 5-octave (61 keys) double (3 choirs) in 15 minutes, that is 15x60=900 seconds. Divided by the 61x3, this means less than 5 seconds per string, and since you need about 2 seconds to move the hammer from one tuning pin to the next, the time to pluck the strings and turn the hammer is less than 3 seconds! Wow! I cannot understand how you can achieve an accurate tuning in such a hurry: guess I am also a slow tuner!

Anywhere between months and a few days. Once I don’t like what I’m hearing, I check with Pitchlab Pro which I changed to from ClearTune about a year ago. Much faster with Pitchlab! But if the poor beast is off 10 cents, I have to retune a few days later. Once tuned and humidity kept under control, there’s maybe a dozen or so strings to fix. Anywhere from 2 hours to half an hour. A lot depends on how sticky the tuning pins are.

Rameau tuning as supplied by Claudio to Pitchlab. 392

I agree with others’ sentiment that tuning speed should not be seen as a virtue in and of itself. I’m saying this because at 60, I am observing a tendency in myself to get more fussy about precision on the one hand, while on the other my ears sometimes get tired sooner. If I for some reason am still sitting there after, say, 45 minutes tuning my two-manual harpsichord, I force myself to take a break.

Additions to the statistics:

I’ve used Rameau for a recording of the first Suite from pièces de clavecin, I now remember.

And for my most recent Couperin I tuned more or less after what Cleartune calls Rousseau (II, III, IV, I couldn’t hear a difference, must be a software bug) for two of the Ordres, and 1/5 SC homogenous French for one Ordre.

When I recorded the Rameau suites in E, D and A in the mid 90s, I used 1/4 comma meantone and re-tuned some accidentals following the requirements of the piece. It does sound good, but I would never do this today…not for Rameau at least.

Also, fortepianos: I actually tune equal temperament on those, either by using Cleartune (it’s really helpful if the pitch is way off, because one can tune every single tone to the required pitch and then one only needs to re-tune part of the instrument when the case has set to the new tension, instead of the usual merry-go-round that results from tuning up and down in octaves), or by winging it (which leads to more interesting yet sliiigtly unpredictable results).

Thanks Tilman, Anne and George for your late additions.

I will wait a little bit before issuing an updated statistics.

Anne tunes many instruments: I will give preference to harpsichords.

Anne and Tilman use more than one temperament. But theirs is not the case like Davitt (where different temperaments were associated with separate instruments which I counted as such in the statistics). So I will count the temperament they appear to use most frequently (Rameau for Anne, Rousseau for Tilman).

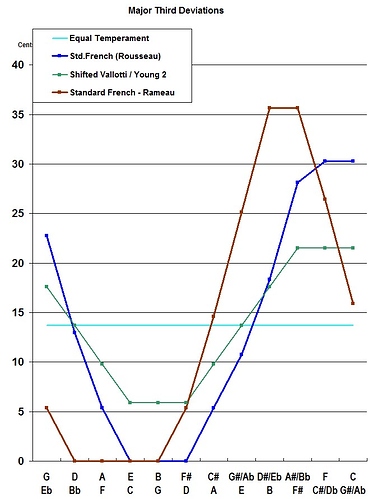

Let me address Tilman’s observation re “Rameau vs Rousseau”. According to my own deductions, Rousseau has three pure major thirds and fifth sizes (thus also third deviations) increase significantly more slowly towards the sharp (asymmetry), while Rameau has four pure major thirds and the deviation is more symmetrical. These two features, however, are not as important as where the “central” pure major thirds are placed: Rameau’s has them at Bb-D, F-A, C-E and G-B, while Rousseau has them at C-D, G_B and D-F#. At this point it is apparent that Rameau is very much accidental-neutral, if not favouring flat tonalities, while Rousseau openly favours sharp tonalities. Also, Rousseau’s three worst maj.thirds can still be played, while Rameau’s two worst ones are already wolves.

I have now produced a special comparison chart which I attach.

But then versions are around (especially of Rameau) that slightly (but significantly perhaps) differ from my own, so who knows?

Thanks everybody for their kind detailed explanations! They may not always be helpful towards a statistics, but reading the experiences of first class musicians is always helpful to us all!

Hello Claudio,

I was a bit surprised to see ‘Belder I’ in the list you made. Maybe it is wise to clarify a bit. ‘Belder I’ is not anything fixed but a kind of temperament in which all tonalities sound well, although not entirely the same. It usually consists of 6, mostly 7 but sometimes 8 smaller 5ths and no wider fifths. It depends a bit on the moment how it develops: merely my mood or reacting on little ‘mistakes’ I made in previous fifths. It is just a practical tuning procedure which I think develops after tuning 400 times a year. So nothing fixed, yet historical. It is actually a standard answer (little joke

)I give when people after a concert ask me which temperament I used. In the end I think it is not such a big deal, only one of the many aspects which is important in a good musical performance. Yet, out of tune is horrible, also when practising. That is why I tune so often (sometimes several times and several instruments a day)

)I give when people after a concert ask me which temperament I used. In the end I think it is not such a big deal, only one of the many aspects which is important in a good musical performance. Yet, out of tune is horrible, also when practising. That is why I tune so often (sometimes several times and several instruments a day)

Best,

PJ

But don’t these statistics do need to include that after-concert standard answer!? Of course they do! Count me in.

I remember a musical amateur who, a decade later, still was miffed because Leonhardt had identified his temperament-of-the-day as “House Special” (“Nach Art des Hauses”) after a recital in Hamburg. And I distinctly recall the ever-changing Overwork-meister III from my early days at the conservatory. And how about Mortified Meantone?

It sure can be a little taxing to explain that one’s personal solutions are something more solid than some mere uninformed ad-hoc decisions. And some concert-goers are pretty persistent when it comes to these details…

Hi Pieter! This temperament statistics I have tried to produce is not the usual “statistician’s statistics” in which the difficulty lies elsewhere (such as the way the sample is taken or how to interpolate missing values at regular intervals), but one where the very basis of the sample is not necessarily “fixed”. Davitt already observed that historically many musicians would not follow a text recipe but rather some more flexible methods. And indeed we all know that in modern times we teach and practice fixed systems (such as Vallotti or Werckmeister III) just because it is easier to follow them and to get a partition that adheres to some specific properties we wish for.

But this is certainly not the only way, especially with experienced musicians like you with a particularly good musical hearing. Your “Belder I” appears to be something that varies between Vallotti (6 tempered fifths) and the kind of very attenuated circular resembling one of Neidhardt’s temperaments or else some partitions occasionally described in post-classical Italy.

One way or the other, in my opinion your “variants” all belong to the “Good Temperaments” in use in German lands in the 1st half of the 18th century. (I mean, Belder I is certainly too unequal to be an “almost equal”, but on the other hand is fully circular and away from 1/4-comma meantone, thus certainly not as unequal and hardly circular as a French ordinaire). You report that “out of tune is horrible”, and I am not surprised: this is the unwelcome consequence of not following a fixed recipe. In most historical “fixed” temperaments (those that do not have significant flaws, such as Kirnberger II), there is no big deal if after a few days one or two of the fifths is 1 cent off: the curve of major thirds will be only slightly affected and you can keep playing. But on the other hand, if you follow a “purely by ear” tuning, inevitably you get a few “weak spots” (for example two consecutive fifths excessively tempered, compensated by nearby fifths), and even a small degradation easily yields a few odd-sounding intervals. Needless to say, this is just a deduction from your short account, so I could very well be off the mark. Please take this just as a personal opinion.

Hi Tilman. At the cost of repeating myself, personal solutions can be very practical and produce excellent results, but they are difficult to teach to others. I fully understand the informed concert-goer who wishes to see whether he/she has guessed correctly (or whether what you have decided agrees or not with what he/she prefers!). Anyway, and again this is my personal opinion, when the answer is not for a statistics among professionals, but for somebody in the audience, I believe that it is enough to respond with the temperament group, such as “Meantone”, “French ordinaire” or “German Good temperament”.

Never temper fifths excessibly! Like CPE Bach describes. Temper fifths and check thirds if they are usable in every key. Not necessarily almost equal. When tuning Belder I, I don’t mean that it entirely depends on how ‘it’ will turn out, in the way of ‘sometimes you are lucky, sometimes not’. Out of tune means thirds unusably wide, fifths unbearable small (or too wide) and octave not pure: so either a bad job or a tuning which fell apart after some time. If I need to retune in two hours, I will do that. I can’t make music on an instrument which sounds out of tune.

Best,

PJ

Couldn’t agree more, Pieter, with a difference. I produce any partition (without electronic aids and without a metronome, sometimes just counting beats against my “mind metronome” according to which tuning method I use) in 5 minutes, with good accuracy. This is the advantage of a “fixed” temperament: not only I tune for a clearly stated set of final deviations, but also I use always the same few tuning sequences, so there is an error prevention of sorts in these procedures at well. The result is that after those 5 minutes I can proceed to tune unisons and octaves and, although I finally check a succession of l.h. and r.h. major chords, I never find any note out of tune at that stage (except easy-to-fix unisons and octaves of course). It may lack flexibility, but it has its advantages . . .

With respect, I disagree. This is a bit like asking somewhat what their religion is, Catholic, Protestant, or Jewish? In other words, it ignores diversity and fits people (and temperaments and religions) into a fixed number of preconceived boxes. We can do better than that.

Claudio suggests that “we all know that in modern times we teach and practice fixed systems (such as Vallotti or Werckmeister III) just because it is easier to follow them and to get a partition that adheres to some specific properties we wish for”. But that was the point my earlier post addressed, last week. No, I don’t teach tuning and temperament like that. Not at all.

Here again is part of my earlier post – I apologize for the repetition, but I think it’s important because I really do believe we make a mistake if we fetishize temperament systems. It is a weakness.

The promised quotation seems to be missing from the end of Davitt’s post. I presume he is referring to his earlier message, which ended: “My approach to tuning is therefore different from what is normally suggested. If anyone wants to try a different yet highly methodical approach that works well for day-to-day tuning, I’ll be happy to describe it in detail. It’s very easy.”

I had expected that someone else would have asked already; but I would be interested to read this description.

The complete message came to the conclusion that tuning for a concert is different from tuning for a recording; but given the repertoire is mainly made up of short pieces or movements, it is highly unlikely that takes from different sessions must of necessity be edited together and therefore, as long.as the reference pitch is the same, and the player can recall what he or she did in tuning for the first session, that should be more than adequate, without needing to decide in advance to tune “Buggins III” or whatever. (Of course, this means that one cannot record this in the booklet, though I doubt that the lack of it would hurt sales!")

As to the general thesis, that one should learn to tune by ear without needing to follow the intricate recipes of the theorists, I can accept that, though I doubt whether the ability will automatically be aquired by learning eight or so of the theoretical tunings – simply because, as Davitt points out, they are theoretical. If we can agree that the oldest tuning in common use is 1/4 comma MT, this could be our starting point, and then experimentation is the order of the day to modify some of the chromatic notes so that they are not objectionably sour when needed for music that has a more extensive harmonic range. After a while, this should become normal practice and, from what I understand, this is the method that TIlman advocates. (He will correct me if I am wrong!)

David

I would be interested too.