I’ve been looking at “Uranie,” the last suite in J.C.F. Fischer’s Musikalisches Parnassus. The courante has the time signature shown in the screenshot. What’s up with this? (The courante in the first suite, “Clio,” has the same signature so it’s not a misprint.) Was Fischer trying to convey the metrical ambiguity of a courante? Labeling it as common meter doesn’t convey this (IMO).

C doesn’t actually mean common time at all, but that the subdivision is in prolatione imperfectum, ie. In 2’s and not in 3s (compound time), a leftover from mensural notation of the renaissance (put simply)

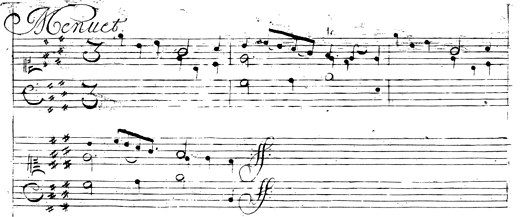

Thanks for the reply. I’ve been looking at more of Fischer’s pieces. He uses C plus 6/8 for gigues, which fits with what you say (an indication that it’s 1 2 3 4 5 6 not 1 2 3 4 5 6). But it also appears in menuets in 3/4 and in the passepied shown below. I don’t see how one could play these pieces in any way other than straightforward triple time (no subdivision in two). So what’s the reason behind the ‘imperfectum’ sign here?

Hi David, in the Fischer example you quote, perhaps the C indicates that though the Passepied is written out in 3/8 bars, in fact these bars should be thought of in pairs (effectively, rewritten as 6/8)- in mensural terms, this would then be tempus imperfectum + prolatio perfecta.

Does this explanation possibly also fit your minuet examples notated in C+ 3/4? It still does not explain what the difference between these C+3/8 & C+3/4 cases and the C+6/8 gigues is, though.

I think the C is a tempo indication and a throwback from mensural notation. We see it in 17th-century music in particular and indicates a very slow tempo. See, for example, Byrd’s The Bells. Both Morley and Prætorius discuss it. There’s no reason to think this is different. We have a tendency to play too quickly these days and, perhaps, forget that while these pieces are often purely instrumental, the designation passepied and courante are indicative of tempo without reason.

We have also to consider how unusual a compound time signature was during the later 17th century, even in Germany.

Are there any other 18C composers apart from Fischer that used this?

Yes, the menuets as well as the passepied can be thought of in groups of two bars (mostly, anyway). Not sure how much difference this actually would make in performance, but it is a plausible explanation.

Jon, thanks for this info. Modern performers may well take many Baroque works too fast, but I have trouble seeing Fischer’s pieces with the C marking as very slow. Or were menuets (e.g.) really danced/played that way?

Also, could you clarify what you mean by “tempo without reason”?

Johann Krieger’s two publications use similar notation. Uniquely, in his Clavier-Ubung of 1698, he places C 3/4 at the beginning of his Giacona and clearly indicates what we would notate as 6/4. Likewise, we would notate the Fantasia in 3/2 as 6/2. Krieger is, however, inconsistent, in that a simple 3/4 is used to indicate 6/4 for the introductory Fantasia (and elsewhere) in the Six Partitas of 1696. In this publication, he sometimes he uses 6/4 and also 6/8 in their modern sense.

I strongly suspect that the works in the Clavier-Ubung, although published later, antedate those of the Partita volume. It has also to be admitted that the notation in the prints of these collections is inconsistent, and barlines are often omitted. Part of this may be due to the copyist, and also to the primitive wooden-block typeface. Nevertheless, Krieger’s metrical intentions (also including black notation in places) are quite evident.

I see no reason to think that C in Krieger indicates a slow tempo – only that the crotchet is the unit, rather than the minim.

David

It appears that modern-style time signatures 3/2, 6/4, 6/8 etc. are not yet fully in use in Germany around Krieger’s time. Johann Kuhnau’s Neue Clavier-Übung (1689 part 1, 1692 part 2) only uses two generic signs, C and 3, apart from in gigue movements, where 6/4, 6/8, 9/8 are used instead. Modern-style time signatures are used increasingly in his slightly later Frische ClavierFrüchte (Leipzig 1696).

In the Neue Clavier-Übung, “3” designates courantes, sarabands and minuets, and this works fine for the courantes (=3/2, with frequent crossrhythms) and sarabands (=3/4), but not so well in the minuets. For example, the minuet in Teil I, Partie 3 would equate to 6/4 in modern notation, but I wonder if it would not be better written in 3/4.

In a way, this is the reverse of Fischer’s Passepied example quoted by David Perry. In the Fischer passepied we might expect the bars to be twice as long as written (ie. 6/8 instead of 3/8), whereas in the Kuhnau minuet (Neue Clavier-Übung Teil I, Partie 3) I would have expected the bars to be halved. But Kuhnau’s notation suggests that they be played in 6/4 here, not 3/4. I suspect Fischer or Krieger might have used the time signature C 3/4 to transcribe this piece, using the C sign to indicate that 3/4 bars be phrased in pairs.

Going back before the Thirty Years’ War devastated Germany, Samuel Scheidt uses the C3 sign for courantes in the Tabulatura Nova, Hamburg 1624, and it makes musical sense here too (not surprising in dance music) to take the 3/4 units in pairs.

It feels as if I am reinventing the wheel here. Does anybody know if there is a definitive study somewhere that has looked at the material systematically? Not that it isn’t fun inventing the wheel, perfect or imperfect.

Yes, I think you are! The thing is that time signatures were more often or not tempo indications.

Jean Rousseau’s Méthode claire, certaine et facile pour apprendre à chanter la musique (1683, 34-36) writes that there are nine time signatures:

C Four beats graves (very slow)

C -barré (Cut C) Two beats lents (slow)

2 Two beats vîtes (quick)

3/2 Three beats lents

3 Three beats légers (quick)

3/4 Three beats plus vîtes (more quickly) than 3

3/8 Three beats beaucoup plus vîtes (much more quickly) than 3/4

6/4 Six beats légers

6/8 Six beats plus vîtes (than 6/4)

Jacques Hotteterre (1719) supplied similar descriptions, the basic concepts of which remain the same: the slowest tempi are represented by C in duple time and 3/2 in triple time, with subsequent time signatures representing a successively faster pace. This matches Saint-Lambert (1702, 19), where he tells us:

The signature of 3/2 contains three minims; one or its value is placed on each beat which must be grave, that is, lent, and just like the [crotchets] in the signature of four beats [C].

We find something similar in Germanic countries as far as Praetorius and in England, Morley, which suggests it was a Europe-wide approach.

JB

I see I have already said this. Apologies … old man … forgetful at times.

Many thanks for these useful references to contemporary explanations.

But, hmm, from what you say Jean Rousseau apparently doesn’t explain what “C 3” means, which is where this thread started out. Kuhnau’s Neue Clavier-Übung uses (except in the gigues) the sign “3” to designate 3/2, 3/4, 6/4 and where necessary seems to specify tempo not by time signature but by indications adagio, allegro etc. Perhaps the ‘similar’ usage in Germany is more conservative than in France? There is also a possibility that actual practice diverged from the recommendations of treatises (which is not to say we should ignore the treatises).

Well, one would assume it to be 3 beats, lents.

As a matter of fact, I am a great believer that treatises should be largely ignored after learning the basics. They were not written for those who possessed both technical skill and le goût but rather for amateur musicians. The same goes for all the ornament tables, which provide starting points for the inexperienced but add nothing to the conversation when it comes to seasoned players. A good example is D’Anglebert’s table which was necessary to explain the ornaments he had almost invented for the publication. Saint-Lambert chides D’Anglebert for showing his port de voix with an on-beat execution though this is not necessarily what D’Anglebert wanted. It was a version of an ornament that can be applied in myriad ways according to the style of the music, the effect, rhetoric and a host of other variables. D’Anglebert gave it in its simplest form since he, like most self-published composers, had a target audience in mind that was largely made up of beginners and amateurs.

I suspect the same applies for François Couperin, whose treatise explains how to play François Couperin’s music and no one else’s. One would never have expected Clérambault or one of his peers to sit and read through L’art de toucher and parse its contents, or play as Couperin wished!

However, treatises are good starting points.

A few years ago, I toyed with the idea of an article discussing the scores of treatises that were published between 1660 and the eve of the French Revolution and read quite a few before realising that they all said pretty much the same. The exceptions being FC and Saint-Lambert, who were more detailed. Nevertheless, when one looks at the latter, there are still chapters devoted to giving out basic theoretical information that and not too much that is of practical advice to players.

JB

Yes, thanks, I will keep a desultory eye out for further comments in treatises as well as music examples. I see the first Courante in Scheidt’s Tabulatura closes both its sections with a hemiola that can be read as 3/2, spread over a pair of two antepenultimate bars, ie in the manner of a French courante.

According to the entry for “Courante” by M.E. Little & S.G. Cusick in Grove, “17th-century courantes were written in one of two mensurations, C3 or 3, and it seems that the mensuration was their first distinguishing feature. Dances in 3, whether in French or Italian sources, tend to be more contrapuntal and use hemiola frequently, while those in C3 are almost invariably simple and lively.” I’m not sure how this harmonizes with the other information though. It tends to run against an interpretation of C3 as slower than 3, I think, and I’m not sure whether it suggests a stronger inclination to hemiola than a simple 3 mensuration would.

It’s a bit of a generalisation and it makes me wonder if the authors had ever seen or danced a courante. French courantes (I dunno about Italian ones) are not really contrapuntal, though some composers used contrapuntal devices. Louis Couperin tended towards short bouts of imitation, but they are mainly homophonic. The hemiola demonstrates this since a switch from one meter to another makes extended counterpoint difficult. Well, it did until Bach reared his ugly head!

I think the courante was more sedate and we see this from the dancing treatises that have come down to us.

Going off on a tangent, I have never seen C3 in a French source (I have to admit to not having seen every French courante ever written). The Germans were funny, though. We see from Buxtehude, Böhm et al. a desire to write in the French manner. Walther in the P801 manuscript even adds French ornamentation in a way that makes it quite clear it was not a natural thing for him.

In this instance, a German source with a C before the time signature is possibly an indication not to play it quickly. They were good at counterpoint but even Muffat has to explain in detail the French aspects of his style.

By the end of the 17th century, mensural time signatures had lost their original value. Composers were happily using compound time signatures, even in England, and void or black notation was used very rarely. When it was (Muffat did), it was to make a point. The C. he used in one toccata (I forget which) was to slow the tempo considerably from the preceding section. Loulié and (if I remember correctly, Saint-Lambert) discuss void notation but are very vague about its meaning.

The problem for us today is that we can bark up mythological trees without thinking that the simplest answer is probably right.

JB

I’m sure there are individual composer’s practices too. It is interesting to see the change in Froberger’s notational practice over time: in suites 1-12 he routinely marks the courantes and sarabands C3, but drops this for suites 13-28, using 3, 3/2 or 3/4 instead. I’m not sure if this switch can be dated. There is some variation in different manuscripts too, for example the saraband in Suite 5 is written in 3/4 with the note values halved (not C3) in MS 16798, Osterreichische Nationalbibliothek.

This is indeed fascinating…

But I just can’t help stating the obvious…

STOP PLAYING EVERYTHING SO DAMN FAST!

Because you can doesn’t mean it’s right…

Sorry… just a major peeve of mine…

I do find it amusing that other than 3 or four beat, and general tempo, everything seems to be remarkably bad at informing performance…

At risk of topic drift (or widening), I agree!

I wonder whether a “never mind the music … admire the dexterity” spirit is related to the quantisation of duration of recording media at about an hour (stretched a bit as the technology has been pushed).

Once the habit of squeezing music of all kinds onto as few LPs or CDs as possible is started, it is easy to see how natural competition between performers could lead to a spirit of “fast is normal”.

Please, let the music (and the mind of amateurs like me) have time to breath!

Re playing too fast - moving to a new thread to avoid hijacking this one.