…but…but…I want to believe that Bach’s favorite instrument was a little clavichord just like mine…;-(

well, any organist in his right mind would have found small clavichords convenient. No need for a bellows and you could play them in bed quietly and warm without waking your spouse, or landlord, or in the pub without being thrown out. One imagines a ten year-old Bach playing his clavichord under the blankets long past his bedtime.

The 2 main problems with clavichords in bed are the sharp corners and the noise they make when they fall out, but this is still nothing compared to the sound of a three-manual Hass or Silbermann falling out of bed. I concede that the latter has however not been documented and may in fact never have taken place.

I think the whole discussion about which early keyboard instrument is ‘best’ or ‘best for Bach’ is very unfortunate. I realise that it has been going on for years, and I’m not trying to single out any of the posters in this thread with this negative remark (surely ‘belligerent’ is too strong a word?). To me there are three points to consider (or to choose to discard):

-

‘What was Bach’s favourite keyboard instrument?’ As someone has pointed out already, this is really an absurd question. Considering Bach’s numerous invitations to adjudicate and advise on new organs, the organ was quite possibly his ‘favourite’, in the sense that he earned the most money from it! ‘Favourite’ can really mean different things on different days. My favourite wine is not the wine I am most likely to drink, for example. Perhaps I can be most expressive on a clavichord - but would that expressivity be convincing in the large hall in which I will play next week?

-

‘For what instrument did Bach intend this piece, or set of pieces?’ In some cases this is very clear (the Goldbergs are for two-manual harpsichord, the chorale preludes are for organ etc etc), In many cases it may not be very clear, or there may be equally satisfactory answers to the question - for example, the Inventions or the Four Duets.

-

‘On which instrument can I play this piece WELL?’ This, to me, is often the most important question. A very fine clavichordist can play all kinds of pieces well on the clavichord; in other hands, some of those pieces might disappoint. The more we look at Bach’s writing, the more we see textures and figurations and use of tessitura which seem to lend themselves more to one keyboard instrument than another. A great interpreter will use these features of the music skilfully. For this reason I don’t really subscribe to the idea that any Bach piece can be played on ANY instrument or combination of instruments - well, it CAN be done, but probably it cannot be done WELL. And ultimately that is, for me, the key issue: Bach has written this music so carefully, with so much craft as well as beauty, shouldn’t we as performers always be looking to do our very best? Why would we choose to do something which is, at best, second-rate?

Having said that, keyboard players often have to make music in the best way they can on the instrument which is available on the day - often there is no other option.

I could not agree more with you Douglas.

I just observe that my comments are consistent with yours and with Ledbetter when he wrote in 2002, as I already quoted (and in my recent WTC edition) , in his Summary to his WTC treatise:

“The argument about instruments is really a product of modern concert life and is remote from Bach’s way of thinking."”.

I cant imagine being able to hear a clavichord in a pub or coffee house above the drinking and carousing! Even for the player, this would be an exercise in imagination, and has the danger of encourging banging.

David

Regarding the numbers of harpsichord and clavichords, and of what types, which were available in Germany at the time of Bach: there has been a great deal of research which takes us well beyond what we can surmise from Boalch.

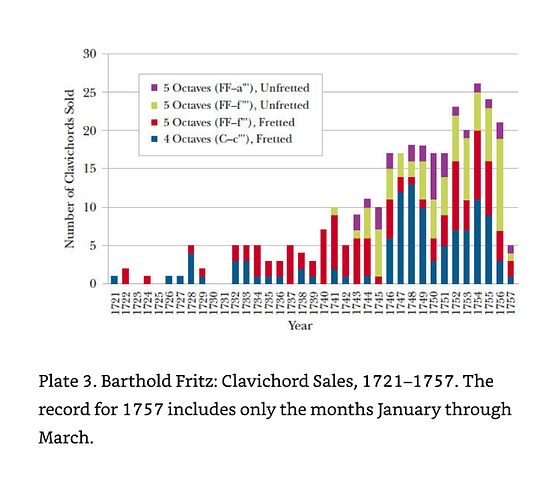

For example, here are the numbers of clavichords sold by a maker in Braunschweig, year by year. (This diagram is from Beyond Bach: Music and Everyday Life in the Eighteenth Century by Andrew Talle - a really important and interesting book, in my opinion.)

You can see that his production really started to soar in the 1740s and 1750s. (He was born in around 1697.) Surprisingly, perhaps, many people ordered four-octave, fretted instruments in the 1740s - because of their small size and low price? (Or was it because they all loved 17th-century music as much as I do?)

I know that Leonard Schick’s Masters thesis for Basel (June 2021) took into account the newspaper advertisements for keyboard instruments in certain parts of Germany. I haven’t studied it in full (it’s in German, will take me a while) but I remember that his research indicates that harpsichords with 16’ stops were more prevalent than once thought.

There is information out there for people who really want to look for it.

4-octave fretted instruments would be useful practice instruments for

organists.

Thanks for the mention of the book. I hadn’t known about it and it does

look really interesting.

Very interesting, Douglas. I observe that all the clavichords sold by Fritz before 1741 were fretted, and about half of them 4 octaves, thus most likely also short C/E octave: this is absolutely compatible with Ledbetter’s observation and what I deduced from Boalch.

I can confirm that. Well, it was a Moller, but still.