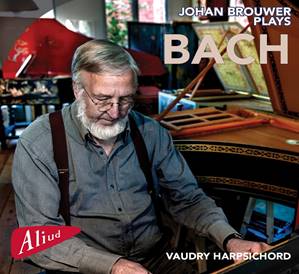

Just tooting my own horn here a little: my new Bach CD has just been announced and seems to be available in Germany (the international release will be in a month or so). I’m playing the 6th English Suite, the Prelude, Fugue and Allegro in E-flat major BWV 998 and Gustav Leonhardt’s arrangement of the second Violin Partita.

Especially suited for contemplative Coronavirus retreat binge listening might be the Bach-Leonhardt Ciaccona, which is the concluding piece of the disk. A few photos and a sound sample on this post on my website:

https://skowroneck.wordpress.com/2020/04/08/new-bach-cd/

Stay healthy, y’all!

Dear Tilman

Thank you for your posting

On my new CD I also recorded bwv 998

I should like to compare the recordings

Johan

Le 08/04/2020 23:57, Johan Brouwer via The Jackrail écrit :

On my new CD I also recorded bwv 998

In our recent discussion of “Bach’s compass”, Davitt Moroney suggested

we leave aside for the moment the question of the instrument BWV 998 was

written for. Now that we are being offered two new recordings of the

work, perhaps we could bring it up. What is the current view? For what

type of instrument was this meant? And what about BWV 996?

Thanks.

Dennis writes: “For what type of instrument was this (BWV 998) meant?”

I admit that I kind of weasled myself out of this question. I’m writing in the booklet: "The mainly supportive role of the bass line in all three pieces shows clearly that the lute was Bach’s first choice. Playing this set on a harpsichord is thus a transfer in which the instrument is exploited in its role as a “keyed lute.” "

I included these pieces because they can function as a conceptual bridge between the English suite (which is as far as we can see an original harpsichord [or clavichord…] piece, but survives in a number of manuscript copies and no autograph: the mildest case, so to speak, of being a transcription) and Leonhardt’s 20th-century version of the violin Partita (which is a full-blown transcription explicitly for the harpsichord [at the time, 1975, recorded on a five-octave French Dowd]).

There are not so many other pieces by Bach (or actually in our entire repertoire) with such a sparse left hand – which is perhaps especially evident for a left-hander like myself. The tessitura is low (like Leonhardt’s transcription of the violin Partita, in fact) which makes that the pieces sound well on many kinds of harpsichords, but that there can be a crunch in the bass register in spite of the few left-hand notes. I remember trying to study them on a short G-octave Ruckers which I had during my first study year in 1980 and I found that they were no fun to play on that compass.

As a lutenist (mainly renaissance and French baroque) but without any claims to be an expert on Bach (unfortunately) I can safely say that all of his works appropriated by modern-day lute players are problematic regarding performance and instrumentation.

BWV 998 is no exception. It is often transposed into D Major to make it more suitable to play on a 13-course lute in d-minor tuning.

Indeed, we really do not know what type of lute should be used. The lute family comprises instruments of considerable variety regarding not only size and tuning but also the number of courses (or strings) and aesthetics. The 13-course is the most popular choice and we know it was used by Bach’s contemporary and acquaintance Sylvius Leopold Weiss but it is far from clear whether that was Bach’s intention. No autograph music has come down to us in lute tablature although BWV 995 and BWV 997 do exist as period transcriptions in baroque lute tablature.

Paolo Cherici’s edition of Bach’s Opere per liuto (Edizioni Suvini Zerboni) has extensive notes on the authenticity and performance problems of Bach’s so-called lute works. Claude Chauvel also wrote some interesting liner notes for Claire Antonini’s CD (Oeuvres pour Luth, AS Musique).

Best,

Matthew

I am surprised that nobody clarified (or perhaps did and I misread and if so I apologise!) that the manuscript of BWV 998, bearing the title “Prelude pour la Luth. ò Cembal. Par J.S. Bach”, was sold in 2016 at Christie’s and fetched an impressive £2,518,500. Guess whoever paid that sum was well convinced that the manuscript was genuine by Bach, and therefore the attribution to the lute appears to be the composer himself.

Best

CDV

Yes, but the question remains, what type of lute and what type of cembalo? There is also the surprising feminine article (luth is masculin in French).

Best,

Matthew

I remember when I was recording this work for Virgin Veritas, back in 1990, that I spent a lot of time staring at those very blatant and audible parallel fifths in the left hand in the first movement. And there is evidence of a modification in the autograph manuscript at just that point, to the tenor part… I wonder what the players who have just recorded this work made of the same passage!

The point still bothers me because we now know the extraordinary extent to which JSB went at just the same time to weed out a totally inaudible set of parallel fifths in the G minor fugue in Book 2 of the WTC. I think he was wrong to do so in the WTC case, and I still happily play those fifths in the G minor fugue because they are inaudible. They fall into the category of what Brahms (in his famous lists of parallel fifths and octaves in the works of great composers) charmingly called “beautiful fifths”. But these ones in BWV 998 really honk, and are less beautiful.

As to the instrument, surely the Lautenwerck must be mentioned here? I think the key of E flat major can be said to more or less preclude the lute in practice, despite JSB’s title. Perhaps we need to remain rather open-minded in reading that title, which certainly has its problems, being a curious mixture of French (pour) and Italian (o), not to mention the mistake (la Luth).

I note that Kim Heindel on his very fine recording on a Willard Martin Lautenwerck for the Dorian label (in 1995) plays the parallel fifths.

How good was Bach’s French?

Good observation Matthew! However, the use of a feminine article is perhaps not significant. J.S. Bach did this kind of errors elsewhere also in either French or Italian. For example in the well known titles he wrote for the Brandenburg concertos:

“Concerto 2do à 1 Tromba, 1 Flauto, 1 Hautbois, 1 Violino, concertati, è 2 Violini, 1 Viola è Violone in Ripieno col Violoncello è Basso per il Cembalo.”

Should be “a” and “e”, “è” in Italian has a different meaning. Then why Hautbois in French when the Italian “Oboe” was already in use at the time?

“Concerto 5to. à une Traversiere, une Violino principale, une Violino è una Viola in ripieno, Violoncello, Violone è Cembalo concertato.”

This is obviously Italian, not French, yet he writes “une” instead of “uno” …

CDV

Who knows, but he was so careful about so much else that the mistake is curious. He spent time with lutenists (there are even suggestions that he taught the lute but this seems improbable) and he must have been familiar with the music of the French lutenists. Are we sure that the title was written in his hand?

The lautenwerck certainly seems like a very plausible solution but there again, do we know what sort of keyboard instrument that actually was? Was it just a harpsichord with gut strings or was it a keyboard instrument with a very large lute-shaped base as some modern makers have used for their renditions (the pictures I have seen of such instruments always look rather ridiculous to me)?

Best,

Matthew

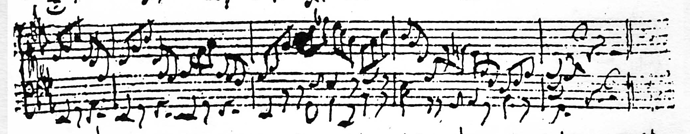

So that’s bar 46, the two-but-last bar of the Prelude, third and fourth beat, between bass and tenor.

Well, it’s certainly not the most stellar moment of the piece. But if we believe that the tenor should be a-flat instead (i.e., a Terzverschreiber), the necessary downward resolution to g on the following first beat (octave-parallels to the treble) would sound even worse; and if we believe the tenor to be intended as the d a third lower, the doubling and almost-parralel (again against the treble, in octaves) resolution wouldn’t be so great either. So I played it as it stands.

Tilman, I’m glad to see you’re thinking about this, too!

After long thought, I came to the conclusion that the only possible other reading is that the tenor E flat on the third beat – which in the autograph MS looks slightly dubious – it’s a bit too big and too black with too much ink – should be an F. In other words, on the third beat both lower parts would rise, in parallel sixths. The harmony is altered but it remains both possible and plausible, once you’ve gotten used to it.

The tenor then remains on F for the 4th beat. Incidentally, this means that the harmonies on the last two beats of that bar are then repeated on the last two beats of the next bar, just before the cadence, with the right hand an octave lower. There is a first inversion of F minor on the third beat each time. When you think about it, that tenor E flat is odd beneath the right hand outlining an F minor chord…

I hope this image comes through OK. It’s the first time I try an image on this new list.

Davitt wrote:

After long thought, I

came to the conclusion that the only possible other

reading is that the tenor E flat on the third beat – which

in the autograph MS looks slightly dubious – it’s a bit

too big and too black with too much ink – should be an F.

The note also doesnt have a very impressive tail.

The tenor then remains

on F for the 4th beat. Incidentally, this means that the

harmonies on the last two beats of that bar are then

repeated on the last two beats of the next bar, just

before the cadence, with the right hand an octave lower.

There is a first inversion of F minor on the third beat

each time. When you think about it, that tenor E flat is

odd beneath the right hand outlining an F minor chord…

The voice leading is not right either. If the e-flat were correct,

it would be a 7th and should resolve to a d. Whereas two fs produce

quite normal harmonies of IIb, V7, VI – the interrrupted cadence

being the excuse for the last bar.

I hope this image comes

through OK. It’s the first time I try an image on this new

list.

It came out perfectly inline here.

David

Le 09/04/2020 16:56, Davitt Moroney via The Jackrail écrit :

After long thought, I came to the conclusion that the only possible other reading is that the tenor E flat on the third beat – which in the autograph MS looks slightly dubious – it’s a bit too big and too black with too much ink – should be an F. In other words, on the third beat both lower parts would rise, in parallel sixths. The harmony is altered but it remains both possible and plausible, once you’ve gotten used to it.

The tenor then remains on F for the 4th beat. Incidentally, this means that the harmonies on the last two beats of that bar are then repeated on the last two beats of the next bar, just before the cadence, with the right hand an octave lower. There is a first inversion of F minor on the third beat each time. When you think about it, that tenor E flat is odd beneath the right hand outlining an F minor chord…

I confess that I’ve never really been bothered by these fifths. Still,

another possible solution to avoid them, or at least sweep them under

the rug, would be to play the tenor’s E flat and replace its 8th-note

rest with an F (repeating the rhythm of the previous beat). This would

also eliminate the unresolved seventh. Of course, this can’t possibly

have been Bach’s intention, so it seems rather arrogant to want to

correct him…

I don’t think it’s arrogant. Bach himself was constantly correcting his keyboard works. As I showed in the notes to my Henle edition of the Art of Fugue (1990), the fine autograph manuscript (c.1745) still has seven or eight sets of parallel octaves or fifths that had slipped by, and they were ALL corrected for the printed edition, proving he wanted to do this. There are several things in Book 2 of the WTC that still seem to have slipped by his eagle eye. Book 1 is pretty well perfect, but that contrapuntal perfection was reached after four different sets of corrections by JSB, each time at several years interval. Off the top of my head I can’t remember the exact dates but the fair copy was made in 1722 (date on the title page). There are corrections on it dating from the late 1720s, again certainly in 1731 (the other date on the MS), and then again around 1735 I think, and perhaps even in the early 1740s. Some of the latest modifications correct frank errors of counterpoint that he had missed right up to the latest stage.

The same process can be observed in the various revisions to the French suites, some of which correct definite contrapuntal errors.

The Prelude Fugue and Allegro only has that one autograph MS, and almost certainly didn’t get a revision. It would be understandable if something slipped by. That is critical to assessing a piece like this. I would hesitate much more with something like the Partitas, which exist in various versions but were printed and reprinted under JSB’s supervision, and so had the vast majority of hitches ironed out. So for us it’s a matter of learning to be critical (in the good sense) about the sources. We cannot approach the WTC 2 in the same way as the Partitas, or the Musical Offering, and WTC 2 requires a more critical eye than WTC 1. The PF&A is an even less revised score than WTC 2. So it has nothing to do, I think, with arrogance. Rather, it is a careful critical assessment of the nature of the source.

I don’t see Bach’s greatness or genius as meaning he didn’t make mistakes. He wasn’t infallible. But I do see his greatness as manifested partly in his desire to keep correcting, keep improving, keep refining. Incidentally, it’s something specifically remarked on by Forkel in his famous biography (1802).

So finding something in an unrevised MS by JSB, like these fifths, is remarkable because (a) it draws attention to how amazingly good his first versions were, (b) it shows us that yes! JSB could still write parallel fifths (but we know that he invariably weeded them out on revision); and © it helps us better understand his work processes.

Best wishes,

D

Thanks Davitt, I agree very much with what you say!

For the sake of the turn this discussion took early on, I have now added the BWV 998 Prelude from my recording at the same link all the way below. It turns out that there’s some conspicuous muffle-up legato going on in the left hand in that bar with the fifths; that’s me trying to save his counterpoint.

Cheers all, Tilman

Interesting discussion! I agree with Davitt that sometimes we have to be a little skeptical of the notes on the page (not just for Bach), especially if the work was not published or we don’t have a revision history for the manuscript. Obviously our skepticism should have some justification before we start rewriting every piece in our repertoire!

I played this piece many years ago, and just looked back at my score. The parallel fifths did bother me and I did avoid them. While Davitt’s suggestion of changing the 3rd beat to an F in the tenor is good voice-leading, personally I like the rich harmony implied by the notated E flat against the F in the right hand (when the tenor and bass have a rest). So I see that I marked a change only on the 4th beat, where I played a B flat in the tenor (instead of the notated F). It isn’t brilliant voice-leading but acceptable, and I prefer to keep what is notated on the 3rd beat.

Douglas