| CDV Claudio Di Veroli

| CDV Claudio Di Veroli

September 21 |

Many thanks to Claudio for sharing his excellent photo of the Urbino clavichord intarsia.

This clavichord is famous for being the oldest depiction of a fretted clavichord, and about one century earlier than the earliest extant such instrument. The compass is F-G-A-Bb-chromatic to c’‘’: four octaves with a short octave from low F. There was no standard pitch at the time, but a working modern replica by Pierre Verbeek is strung and pitched for A=440Hz. (see https://harpsichords.weebly.com/urbino-palazzo-ducale-clavichord-15th-c.html : for more details Verbeek’s full paper of 2011, entitled “The Urbino clavichord revisited”, is available for viewing and free download.

The reconstruction may well have been at A=440Hz, but Verbeek writes “The pitch might have been a2 = 440 Hz or higher.” I would say much higher. With an f’ string of about 336 mm and iron treble strings (Sebastian Virdung, Musica getutscht (1511), refers to the use of both iron and brass strings for clavichords whose strings are not all tuned in unison), the instrument could have been tuned as much as a fifth above a’=440Hz, If strung in brass throughout, it might perhaps have sounded at the Arnolt Schlick’s (1511) two pitches, in the region of a minor third above A=440Hz,

In a subsequent message Claudio notes “It is even possible (not that easily in my picture, it would require an even greater resolution) to count in the intarsia the 17 courses, as described by Verbeek.”

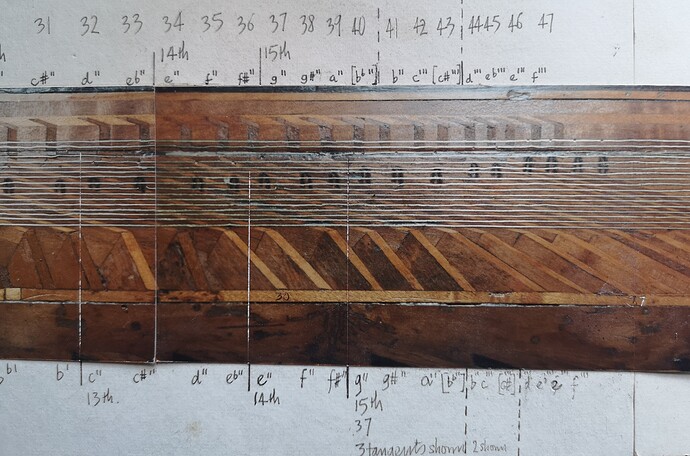

I can offer (with apologies for this being a quick phone-camera copy of an annotated 1985 print) this photograph, which was taken close to the intarsia, with the Perspex screen temporarily removed.

Not surprisingly, given the low angle from which the instrument is seen, the artist simplified the 17 paired courses to 17 single strings, all clearly visible here except for parts of the third from the rear (near the top of the photograph), which is partly missing.

My 1985 annotations might be of interest.

The vertical lines mark the grouping of the frets in 4s and 3s.

The bb’’ and c#‘’ tangents were omitted. Verbeek observes that “We are inclined to believe that the fact that two tangents are missing is not due to an accidental omission. This anomaly, in our view, is not fortuitous. Be that as it may, in practical terms, it means actually that this clavichord is not in playable order.”

It is likely that they were omitted not to show an “unplayable” instrument but because, had they been included they would each, because of the clustering of the tangents in relation to the strings, partly have clashed with the tangent below. I suggest that they were omitted for essentially the same Not surprisingly, given the low angle from which the instrument is seen, the artist simplified the 17 paired courses to 17 single strings, all clearly visible here except for parts of the third from the rear (top of the photograph), which is partly missing.

My annotations might be of interest.

The vertical lines mark the grouping of the frets in 4s and 3s.

The bb’’ and c#‘’’ tangents were omitted. Verbeek observes that “We are inclined to believe that the fact that two tangents are missing is not due to an accidental omission. This anomaly, in our view, is not fortuitous. Be that as it may, in practical terms, it means actually that this clavichord is not in playable order.”

It is likely that they were omitted not to show an “unplayable” instrument but because, had they been included they would, because of the clustering of the tangents in relation to the strings, partly have clashed with the tangent below. I suggest that they were omitted for essentially the same practical reason as the other 17 strings.

Note also the spacing of the slots in the rack at the rear. The tuning is Pythagorean, in the same Gb-B configuration seen in the earlier Arnaut of Zwolle manuscript. For example, the first three semitones (at the top left of the photo), between c’’ - c#’ - d’’ - eb’‘, are minor - major - minor. Although the c#‘’ was evidently intended to sound a consonant third (virtually 4:5) above a’, it is, in Pythagorean spelling, strictly a db, a fifth below ab.

Note also the spacing of the slots in the rack at the rear. The tuning is Pythagorean, in the same Gb-B configuration seen in the Arnaut of Zwolle manuscript. For example, the first three semitones (top left of the photo), between c’‘, c#’, d’‘, eb’‘, are minor - major - minor. Although the c#‘’ was evidently intended to sound a consonant third (virtually 4:5) above a’, it is, in Pythagorean spelling, strictly a db’'.