Looks very interesting indeed!

Best

Claudio

To play devil’s advocate, what does this edition bring that we cannot obtain from the original edition, which is available here? (Even though, for once, the price asked seems pretty modest.)

Hi David: I do not have a copy yet. I guess it is pretty much the same of other modern editions. Indeed, the original is in the modern clefs G and F, but the note alignment does not follow modern conventions, and can be confusing for amateurs. Also, the correction of errors, however minimal. And a useful introductory text.

Years ago, when I was not as able to sight read as later, I bought the OUP facsimile edition of the John Stanley Voluntaries, opp 5, 6 & 7. It may have been a romantic impulse, but I found it much more interesting to play from the notation of the period, and have always preferred to do so. Modern editions of these and other organ voluntaries always looked more prosaic and less interesting. In the facsimile, the non-alignment of the parts in the first movement of op. 7 no. 4 are as extreme as any I have seen. I enjoyed the challenge of learning to think as the players did in those days (i.e. in separate parts, rather than in chords), and it did not take as long as one might expect.

I havent checked the Kellner editions, but 18C printing often has less page turns during the music.

David

You certainly have a point, David. Students should learn to play from original editions. However, critical modern editions have the advantage of introductory texts and, very importantly error corrections. Even when there is an autograph or first edition with author’s corrections (e.g. Bach’s WTC I and Partitas), there are still lots of doubts about dubious details where a well researched edition can help the player.

I cannot state to which an extent this is true of this Kellner edition, of course.

Another problem is legibility, e.g. the last suite (at least in the IMSLP scan which looks well done) …

Not only should students learn to play from original editions, but they should also, maybe even more importantly, develop a strong sense of their own about dubious details in original sources {and Urtext editions}. Of course they should be as critical of themselves as they are of the original sources.

Regards,

Dale

This is true. But the other side of this coin is that notes are often crowded together; to me, at least, such crowded text is difficult to play from.

Until 2-3 years ago I had never worked with facsimiles – partly because I was not a music major in school and partly because in those pre-internet days such reproductions were not readily available.

When I began studying facsimiles, I couldn’t find any article or book that explained the differences between Baroque and modern practices. I was able to figure out most things without too much trouble, but having a guide would have saved me time and occasional uncertainty. I kept careful notes (with musical examples) about what I observed and have thought about putting these notes into a more formal shape. The professionals on this list know this stuff already, but I wonder if such a booklet would be useful for other amateurs or students. Should I pursue this project?

Hi David (Perry)- good idea! If you have kept notes of the questions that arose for you, I’m sure a booklet of this kind could be very useful for other players engaging with facsimiles.

This is an interesting topic. I suspect that 18th-century players would have smiled at our expectation that everything must be perfectly legible; they likely had to contend with much greater legibility problems (scribbled tablatures…) and so had correspondingly better memorization and guessing skills (certainly better than me, anyway).

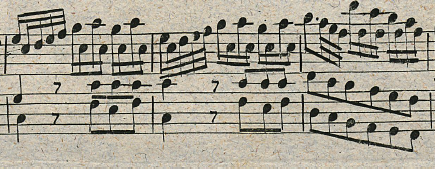

To me the Kellner facsimile looks very legible indeed. Having said that, there are still some ambiguous (faulty?) passages, and, as Claudio says, it can be useful to have an editor make decisions about them if you don’t want to choose for yourself . For ex. in suite 1, in the Sarabande on page 6, I am intrigued how to play bars 37-39 in the bottom system

and would feel tempted to play the demi-semiquavers/32ths as triplets- but wonder whether an editor who knows the entire collection well would support that reading. On the other hand, if I only had a modern edition to hand I would prefer to know what the original looked like.

Like David Pickett, when starting out on the organ I used the affordable OUP facsimile of John Stanley and was irritated by its habit of placing semibreves/whole notes bang in the centre of the bar, rather than at the beginning. It means you have to read the entire bar as a unit before playing any of it, rather than happily bumbling from one note to the next as was my practice (in that distant time). I wonder how much this notation practice encouraged players to process the music in one-bar units, possibly affecting how they played. Likewise, the practise of superimposing a minim directly on a bar line and straddling two bars affects the player differently than the modern notation of two tied crotchets/quarter notes. It encourages you to zoom out and think in two-bar units where you had previously been thinking in single bars.

Michael

Certamen Musicum - what does that mean exactly in this context? The Latin I did at school does not quite extend that far, as I thought certamen means battle, combat, or dispute or contest, or possibly discussion.

Speaking as a person that nowadays spends most of my time engraving, with Lilypond and Dorico, and consequently devoting a lot of thought and energy to engraving issues, especially off old editions (I am doing the complete Haydn string quartets from the French Bonaparte edition by Pleyel of about 1803 currently [a pretty big project involving a lot of time dealing with all the errors and inconsistencies!]) I find this original interesting, in that it appears to span from 1743 to 1749, each suite having a different year, and the hand of the engraver looks different in each case.

While I like old editions and facsimiles, this seems to be, compared to other editions of the time, very amateur engraving, and very inconsistent and not particularly attractive. I know that Kuhnau liked to do his own engraving and learned how to do it. I wonder if Kellner engraved these himself?

This complete goof up in the courante - avoids a page turn, yes, but… - is an indication of an unprofessional engraver at work:

Some of the Preludes are called C. D. Praeludium. What does C. D. mean?

Absolutely! But in this day and age such a document might find more readers as a page on the internet which could be “updated”.

Not only Kuhnau: Telemann was incredibly prolific as an engraver.

It could just be a Friday afternoon job – a miscaculation of space needed, and a reluctance to start again on a new plate. We know that individual mistakes were often corrected by hammering the plate; but these are often still visible, and it is doubtful whether a whole plate could be erased successfully in this painstaking way.

Again, in my extreme youth, I copied out quite a few pieces in the British Library, and frequently resorted to such tricks as we see here to fit everything on the page. Even JSB did the same, often using organ tabulatur at the end of the page. The point is that, with a bit of practice, it is not difficult to read such inelegant work.

I think it goes further than that. It is not only semibreves that are placed at the centre of the space they occupy: all notes are centred in their space, rather than being left justified or aligned to their start, as is modern practice. This is why I think musicians must have thought in terms of voices, rather than chords.

I made a mistake earlier in quoting Stanley’s op.6 no.4 wrongly. I reproduce it here for those who would like to try reading it at sight.

Only the first and last preludes of the set have this enigmatic C. D. The internet suggests Comitialibus Diebus, but I can come up with no translation for that. There appear to be no common musical features between the two examples.

Whereas most of the movements have no dynamic markings, three of them prescribe terraced forte and piano markings.

Delving deeper on the “C. D.”: possible explanations.

-

“Comitialibus Diebus” as suggested by David P. This is forensic/legal Latin for “during the days where we have meetings”. Surely this is not the meaning here.

-

The other use of the abbreviation in Latin is “Caesaris Decreto”: this means “by command of the Emperor.” Perhaps Kellner wrote Suites I and VI for the Emperor? But then why is the C.D. attached to the Preludes only? He wrote those 2 Preludes for the Emperor? Does not look likely…

-

Kellner mixes French and Italian names. What about Italian? C. D. in Italy stands for “cosiddetto”. In this context, C. D. Praeludium means something that we call Praeludium but is not quite a Prelude.

The fact that this appears only in Suites 1 and 6 makes good sense:

In Suite I Kellner calls this an Andante.

In Suite VI this is a succession of arpeggiato chords, not what a typical 18th c. German would call a Praeludium.

This is the explanation I find most likely.

Happy Sunday! Some momentary glances of sunshine here in Lucca! ![]()

The arpeggios of one and the repeated figuration of the other seem to me to be typical “preludising”.