Does anybody know of sources of information about music wire manufacture in the period ca.1200-1500? I am looking at surviving evidence of tuning methods for European wire strung psalteries in the 13th and 14th centuries (diatonic scale, roughly 19 strings). As might be expected, I am at a loss about many basic stringing matters: what was wire quality like, how fine and reliable were the gauges used, etc. (I think there is no surviving instrument or instrument wire from the period- hope this is incorrect!) I am reasonably familiar with the material Christopher Page has gathered on the subject (in Voices and instruments of the Middle Ages, and articles) but am sure there is more out there, and more to be said about what has been found.

For what it’s worth, Egidius of Zamora (late 13th c., music teacher to the son of Galician Alfons X the Wise) says in his Liber Artis musicae that psaltery strings are of brass or even silver. But it would be interesting to know whether psalteries (and their keyed descendent, the clavicymbalum) had a lot of inbuilt inharmonicity.

Grateful for any pointers and comments, practical or scholarly. Michael

Hi MIchael,

A practical comment: to make wire, one needs ore, wood to melt it, and preferably a watermill to blow the four to a high temperature, and equally a watermill to get the power to draw wire in large quantities or medium thickness. So wire is produced in cities where all these elements are present. In Europe it was Nurnberg, but also in other cities.

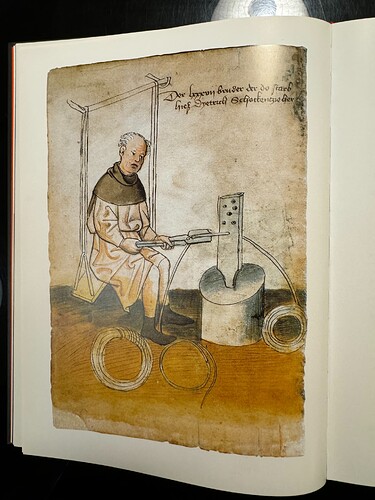

The most important use of wire were not musical instruments but chain mail armors. The monk Theophilus Presbyter described in 1122 the process of manual wire drawing in Germany. Manual drawing continued until 1500. In 1425 we know a swing which allowed for stringer wires (see attached file). It seems to be invented around 1360 in Nurnberg. Drawing with waterpower dates from the 15. century.

A history of wire drawing in Germany can be found in ‘Draht, vom Kettenhemd zum Supraleiter’ (2001, in German).

However wire drawing by hand is much older, and seems to be known by the romans and in Egypt and Syria. That was typically gold wire for decoration of clothing.

The key question is, and I do not have the answer: with which pace went the evolution from weak, to stronger wire in those days? How strong could a metal string be in 1200, how strong in 1400?

We know that brass wire used by the ancient Egyptians and there are surviving artefacts. Much earlier than iron wire.

Thanks, Andrew and Pieter- this is exactly the kind of information I was hoping for. I am still wondering if there is any medieval wire surviving from wire-strung Irish harps (impossible to date, I expect).

This image from Wikipedia, 1570. Observe the coil of wire and very modern looking tuning hammer!

Naught about strings here, but fascinating history covering the period you are interested in, regarding iron specifically.

With limited compasses as even the large ones had, I imagine you could get away with one gauge, and standardisation of diameter would hardly have mattered.

In harmonicity in music wire tends to arise when the thickness is relatively large compared to length and things depart from the idealized infinitely thin string of physics simplified analysis. I can’t imagine anybody giving a fig about inharmonicity in 1200 AD.

Wikipedia shows a late text with the tuning notes, but do we have any idea at all what notes people tuned in general?

How accurate this information is I am not sure, but of interest nevertheless.

https://earlymusicmuse.com/psaltery/

Since the psaltery is the great grandaddy of harpsichords this is a very valid topic!

I imagine early ones had gut strings.

Thanks Andrew- Yes, it is thoughtful and the information is good though some source references could be fuller.

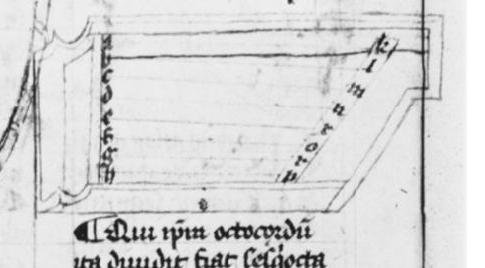

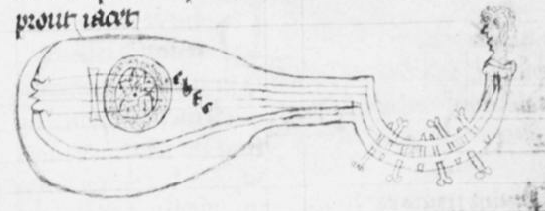

It mentions important diagrams of instruments in a 1360s manuscript, Berkeley MS 744, including an intriguing transitional psaltery/clavicymbalum (no keys illustrated in this MS, but they are in a 15th-century MS copy of the text). A bit like a schematic antecedent of Arnaut von Zwolle, not drawn to scale.

The full Latin text of Berkeley 744 is online at https://chmtl.indiana.edu/tml/14th/BERMAN This is extracted from the edition, commentary and English translation by Oliver Ellsworth, which I haven’t seen: The Berkeley Manuscript, ed. and trans. by Oliver B. Ellsworth, Greek and Latin Music Theory. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984.

A closer look at the image together with accompanying text shows this psaltery doesn’t only have 8 straight (parallel) strings abcdefgh but also a diagonal cord kb, and we are told there are similar diagonals on the other strings (which the text implies can also be sounded- ie, not resonance strings). If I understand the text correctly, this is a “Ptolomean” division of the octave, where each diagonal string stands in a sesquioctave ratio to the straight string below it (sesquioctave= 1+1/8, or 9/8) But I haven’t sorted this passage out properly yet, nor do I know why the letters klmnrorp are in that sequence. Anyway, this anomalous setup is determined by its context in a 1360s history of Greek tunings.

There is also a psaltery tuned to include cc# (not dd) on the highest string, as well as a B molle and B durum. Again, this figure needs to be interpreted in the context of the accompanying text and might not represent a normal instrument; but there is an earlier music treatise (Amerus, 1271) that illustrates psalteries with C#s.

:

Oops, a correction: the Berkeley MS 744 (a collection of 4 separate music treatises) was written up to 1375 at the end of the third treatise, not in the 1360s.